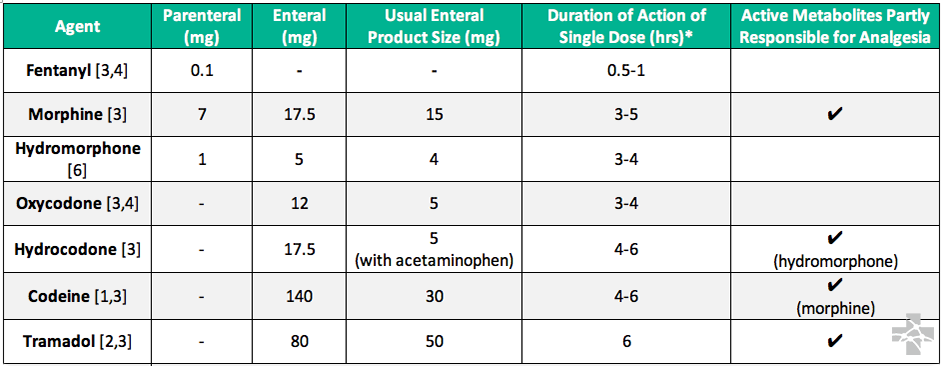

Opioid Analgesics for Acute Pain: Relative Potencies

Why are so many opioid conversion recommendations different?

Many opioid conversion tables exist to transition, or rotate, between existing chronic pain regimens. The data used in these tables are derived from both single-dose and chronic, steady-state opioid regimens that may not be applicable in the Emergency Department. The information below is taken when possible from published evidence using single dose or acute pain as encountered in the ED.

* Not half-life time

Not recommended for opioid-equivalent conversion in the acute setting

- Methadone: If opioid medications are necessary, short acting (oxycodone, hydromorphone) agents and frequent reassessment should be used. The patient may have tolerance to opioid agonists, but side effects will be additive.

- Buprenorphine: Buprenorphine is a partial agonist with tighter binding affinity than full agonists. If opioid medications are necessary, short acting agents and frequent reassessment should be used. Note that since buprenorphine has a tighter binding affinity, full agonists will have less effect.

Pharmacology

All of these compounds bind the mu-opioid receptor (among others) which is responsible for both the analgesic effect as well as sedation and respiratory depression. The potency of each compound at the receptor describes some of the dosing differences.

For example, fentanyl is 50-100 times more potent at the mu-opioid receptor than morphine.

Pharmacokinetics [1-3]

Absorption and distribution affect “apparent” potency

Both administration route and chemical characteristics like lipophilicity affect “apparent” potency.

- Morphine administered IV will have a more rapid time to maximum concentration (Tmax), and higher serum concentration (Cmax) resulting in a quicker onset of action. The effect will be a more rapid onset of action and a higher “apparent” potency than the equivalent morphine oral dose.

- Fentanyl is highly lipophilic and crosses the blood brain barrier quickly resulting in a very rapid onset of action when administered IV. This makes it appear more potent than an equivalent dose of morphine administered IV.

Metabolism accounts for some clinical effect differences

Some opioids have active metabolites that are at least partly responsible for analgesia and thus toxicity. Differences in metabolism will alter their clinical effects. For example, cytochrome P450 2D6 is responsible for metabolism of codeine, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, and tramadol and is highly genetically variable.

- Approximately 5-10% of patients are CYP2D6 poor-metabolizers, resulting in little metabolism of codeine into morphine and very little to no clinical effect.

- Conversely, 1-5% of patients are CYP2D6 ultra-metabolizers, resulting in a significantly greater codeine metabolism into morphine and potential toxicity.

- CYP2D6 is responsible for tramadol metabolism and a poor-metabolizer will have less analgesic effect due to lower concentrations of the active metabolite, but the risk of adverse effects such as seizures remains. An ultra-metabolizer will have higher concentrations of the more potent active metabolite, potentially resulting in toxicity.

References

- Dean L. Codeine Therapy and CYP2D6 Genotype. Medical Genetics Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2012. 2012 Sep 20 [updated 2017 Mar 16]

- Dean L. Tramadol Therapy and CYP2D6 Genotype. Medical Genetics Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2012. 2015 Sep 10

- McPherson ML. Demystifying Opioid Conversion Calculations: A Guide for Effective Dosing, 2nd Edition. Bethesda: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2018

- Patanwala AE, Duby J, Waters D, Erstad BL. Opioid conversions in acute care. Ann Pharmacother. 2007 Feb;41(2):255-66. PMID 17299011

- Kalso E, Vainio A. Morphine and oxycodone hydrochloride in the management of cancer pain. Clin Pharm Ther 1990;4:639–646. PMID 2188774

- Hanna C, Mazuzan JE, and Abajian J. An evaluation of dihydromorphinone in treating postoperative pain. Anesth Analg. 1962; 41: 755–761